Playing Sex and Winning Grief

There was a dark era in American history where mainstream media went ridiculously far out of its way to hate video games. If you believed late 90's/early 2000's television, the people who played games were nerds, the people who made them were even nerdier nerds, and if your kids played too many violent games then they might murder your neighbor’s cat and worship the devil. We’ve moved on from those dark days, and we’re inching ever closer to a world where you can play games without your parents scolding you for “wasting your time” or some frat guy calling you a "dweeb" and giving you a wedgie. Though this bright day gleams on the horizon, I think we’re still in a transitional period. Games are still a vastly underappreciated art form, especially when it comes to storytelling.

Think “video game story.” If you don’t play games, and your parents are of a certain generation, chances are you’ve probably conjured up something involving square chinned alpha males impaling monsters with swords or running over pedestrians or shooting brown people. These kinds of games are never going away, and that’s fine. (Or at least it's fine so long as they stay in the realm of good taste.) However, if games are ever going to be accepted without any reservations, then the perception of what video game stories can accomplish needs to be expanded. When I tell my non-gaming friends and family about a husband and wife who made a game about their five-year old son dying of cancer or a woman who made a game about the time she fell in love with someone over the internet, I’m met with a resounding, “Huh?”

The more I explain that these smaller games exist to my non-gaming brethren, the more I understand that the hard part for them to grasp is not the fact that games can tell meaningful stories. The hard part is explaining what you are actually doing in the game and why it matters. How does one “play” a child dying? What buttons do you hit to fall in love? How can we tell grounded autobiographical stories with an interactive medium?

Let’s start with That Dragon, Cancer, which tells the story of Ryan and Amy Green, the lead designer and writer respectively, who lost their five-year old son Joel to a terminal brain tumor. The story unfolds through fourteen chapters, bringing us through Ryan, Amy, and Joel’s journey from the first round of treatment to Joel’s eventual death.

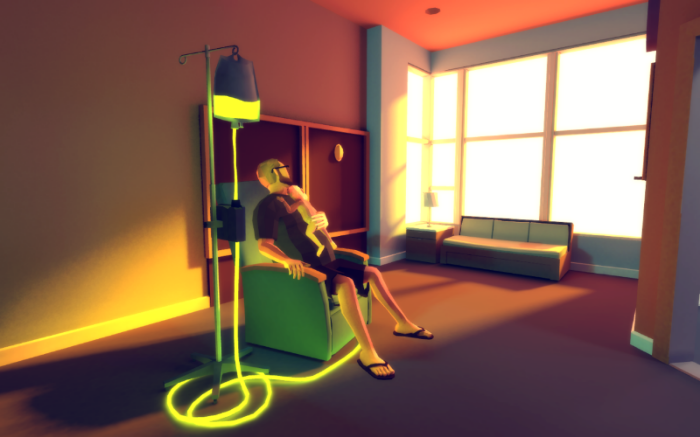

Ryan and Joel.

In each chapter, we navigate through a location in the style of a point and click adventure game. If you want to go to a space in a room or interact with an object, all you have to do is click it. Sometimes we’re playing as Ryan or Amy. Sometimes we’re floating in a dream like fashion while scenes unfurl in front of us. Using simple interactions, the game connects us with the emotional state of Joel and his parents.

In the first chapter we play as a duck. Joel throws bread into a pond while we, the duck, click on the bread to eat it. As we eat bread, we listen to a voice over of Ryan and Amy explaining to their other children why Joel hasn’t developed as much as the other kids. It’s an effective way to communicate the severity of Joel’s condition while staying in his perspective. To everyone else, Joel is a very sick little boy. Joel’s only concern, however, is feeding the ducks.

In the next of chapter, you play with Joel in the park. You click on the swing to push him higher or the slide to help him go down. You’re not actually doing very much, but it feels like you’re hanging out with a happy energetic kid. You’re helping him have fun, and to me, it felt genuinely serene and heartwarming. However, you know where this story ends. While you play with Joel, there’s an unshakeable sense of dread, and all you can do is enjoy the moment while it lasts.

Though there’s the occasional section where we have to do more than click, most of the chapters involve these simple kinds of interactions, but in increasingly surreal environments. In another section, Ryan falls asleep in the hospital. In his dream, Joel floats in outer space and drifts towards the moon while holding a bunch of balloons. (I believe the balloons are actually blown-up hospital gloves.) Soon comes these weird globular spheres, and if Joel touches them, a balloon pops. You realize it’s up to you to keep Joel afloat, so you move the mouse left and right to steer Joel away from the globs and towards the moon. However, there are so many spheres that it becomes clear you can’t avoid them all. Eventually, all the balloons pop and Joel falls. Luckily you wake up, and Joel’s still with you.

You try as hard as you can to protect Joel, but in the end there’s nothing you can do. I’ve played That Dragon, Cancer a few times now, and each time I reach this section I panic every time a balloon pops. I know it's probably not possible to get Joel to the moon, and he’ll fall no matter what I do, but I still want to keep him floating for as long as I can. Imagine what it must have felt like to be his father.

Despite the heartbreaking moments in That Dragon, Cancer and the sheer gravity of its subject matter, I do consider it the weaker of the two games we’re talking about in this article. It’s one thing to play in someone’s dream, as dreams often contrast with reality in order to offer us insight into the dreamer. Through playing Ryan’s dream, we’re connected to his desire to keep Joel safe, and the helplessness he feels when he realizes that there’s nothing he can do. However, the deeper into the story we go, the more the game doubles down on the surreal. The environments we interact in become increasingly more bizarre, and not only does the story grow more vague as a result, but also the emotional connection to what we are doing.

There’s a chapter in the first half of the game called “The Temple of Man” that begins with Joel playing on top of a giant medical machine. (I’m not sure what kind.) You see some X-rays, then Joel wants to play with an odd light balloon ball thing. The balloon becomes an orb you open, and, long story short, you glide your mouse over these shapes that form animals made out of constellations for Joel to ride. (In hindsight, it was stupid of me to try to explain this section verbally, but I'm in too deep now. Don’t worry, it barely makes sense to me either.)

Here's a picture if that helps. Probably not.

It becomes clear in later chapters that Ryan and Amy are devout Christians. I know the chapter title is “The Temple of Man” while a later one is called “The Temple of God.” I think I can read into that, but I don’t know what or why. I think this section is a dream, and it might have something to with the song Amy hums in the next chapter or a bible verse, but I don’t know what this section is trying to communicate to me. I have no idea what I’m supposed to feel or connect to, nor do I know where I am in the overall narrative. Maybe you, dear reader, have some insight into what’s going on that I don’t, but I know that I became resentful at the game for taking a purely emotional experience and turning it into an pseudo-intellectual exercise.

Later chapters return to a section where you travel towards a lighthouse in the middle of the ocean. (Chapters eight, ten, and twelve to be specific.) You play as a bird. You click on areas and objects to land on while Amy holds Joel and floats towards the lighthouse in a rowboat. On your way to the lighthouse, you land on buoys and click on messages in bottles to read them. Some of these messages are thoughts on god written by Amy. Some tell stories about friends and family who have lost loved ones to cancer while others contain poetry. Sometimes, you dip below the surface to find Ryan, surrounded by the globs, drowning in the water.

On paper, I think the metaphor is clear enough. Amy’s faith in god and the prayers of others keep her gliding on the surface while Ryan drowns in despair. However, I don’t connect to these moments with the actual gameplay. I’m merely a bird flying around while the story plays out in front of me. I’m not in the moment like I was when I was playing with Joel in the park, and because of that, I feel at an arm’s length. Now I want to criticize. Now I want to point out that it’s not clear all the time where I’m supposed to click and the actual playing of this game is beginning to feel like a chore.

With the exception of chapter eleven, this is generally how the second half of the game works. The gulf between gameplay and story grows wider and more abstract. I suppose one could argue that you lose more and more control just as the Green family did, but I still feel that weakens the experience of playing the game. Even with those caveats, That Dragon, Cancer is still powerful and heartbreaking and you should play it. Specifically, you should buy this game and play it rather than watching someone on Youtube. It’s not a perfect experience, but it’s one you should absolutely have for yourself.

And you know what else you should play? Cibele. You should play Cibele.

Nina Freeman.

In Cibele, you play as Nina Freeman, the game’s designer. It begins with some filmed footage of Nina on her computer. The game then gives us control of Nina, and we can explore her computer just like you would your own. If you feel so inclined, you can go through some of Nina’s files and learn about her life. We discover that she writes poetry and goes to college in New York and really really likes anime. Or you can skip all that and click on the big attractive looking icon on the bottom left hand corner, which opens a fictional online multiplayer game called “Valtameri.” Her user name: Cibele. While you play the game in the game, Nina starts voice chatting with another player, Ichi, who we’ll later know as Blake. As Blake and Nina converse, you can reply to fictional messages and emails and do the kinds of things you would normally do on your computer.

The game divides into three chapters, spanning about six months in time. In each new chapter, you can explore new files where we can see what’s been going on in Nina’s life. To move the story forward, you open Valtameri. You play the game, Nina and Blake talk, and we listen as their relationship progresses until it reaches a climax. (Snicker snicker.)

Although Cibele isn’t very long, I found it incredibly engrossing and powerful in a surprisingly subtle way. While exploring Nina’s computer and playing Valtameri allow you to put a tic in the “interactivity” box, many of Cibele’s gameplay mechanics were effective for me because of my personality and the way I play games.

Let’s start with a simple one: I rarely play multiplayer games. Sometimes I’ll go in for an online shooter or something like that, but a single player campaign is what I want, and rarely do I go for anything else. (That said, you’ll pry Rocket League from my cold dead hands.) I’m also not texting or chatting when I’m playing a game. I am completely alone. With the shades pulled down. And the lights turned off. Organ music playing. Scowling.

Joking aside, if you call or text me while I’m playing something I’ll get annoyed and grouchy. Gaming for me is a very one-on-one experience. Even when I’m playing my beloved Rocket League, most of the time I’m doing so on mute so I can listen to albums or podcasts.

Nina, or at least the version of Nina in Cibele, seems to play the opposite kinds of games in the opposite kind of style. On the surface, it might seem like this would turn me off the game, but what it actually does is engross me further into the experience. I was playing Cibele as myself, but I was playing Valtameri as Nina. Nina responds to messages while playing games, so that’s what I started to do myself.

In fact, this oddly absorbing contrast I have with fictional Nina goes one step further. Let me tell you all a story about myself: A few years ago, I had an internship where I worked Monday through Thursday. Friday came around, and I realized all my friends were out-of-town or busy, so I spent the long weekend watching movies and relaxing. I went to work on Monday to discover I had a little bit of trouble speaking, and I realized it was because I had literally not said anything out loud in three days. To some, this might sound sad and lonely, but I actually loved every second of it.

Playing Valtameri and chatting with Ichi.

I tell you this story because based on what we can learn about Nina in the game, she seems like a relatively sociable and open person. She interacts with the public and people she’s never met face to face in a way that I never would. She literally made a game allowing you to explore her sex life, and I’m one log cabin in the woods away from being a full-blown hermit.

Since Nina is so open about herself in how we interact with her game, it draws me closer to Nina’s perspective. I have no idea what it’s like to be a social person, let alone Nina Freeman, but Cibele puts me in that mindset with the way we interact with it and how the story unfolds. The more I message “my” friends and play Valtameri, the more I can connect with the emotions Nina might have felt in the moment. The concept of a couple, or just casual partners, meeting over a multiplayer game was so alien to me that I couldn’t even comprehend how that was ever possible. Thanks to Cibele, I think I understand.

Cibele is very much concerned with the difference between forming relationships online and forming them in real life, and it comments on this contrast with its use of FMV. (To my non-game playing friends, FMV means “full motion video.” Basically. putting live action footage in your game.) You can interact with the game when you’re on Nina’s computer, but it takes control away from you in the real life sections of the story.

(Spoilers:)

I think the separation of when you can interact with the game and when you can’t reflects Nina and Blake’s relationship. Their relationship seems to only progress while playing Valtameri. Through their voice chats, we hear Nina and Blake say "I love you" to each other, and at least to me, it seems pretty sincere. They've also told each other that they're both virgins. Nina wants a physical and emotional connection in the real world, but Blake tells her that he doesn’t know how to handle that kind of relationship. Nevertheless, Blake and Nina meet in real life, and this is when the game takes control away from us. Through FMV, we see them meet and have sex. Nina finally gets the real life physical interaction she wants out of Blake, but after they're done, Blake says he doesn’t love her and leaves. We watch him go, and we end with Nina sitting in front of computer. Valtamari's opened, but she isn't playing.

We cut to black and some text appears on the screen: "First love is a very confusing thing, and sometimes it really hurts, but I'm glad I had mine with you. - Nina"

Maybe Nina wanted their relationship to last. Maybe not. Maybe if more of the game was in our control we might be able to make either outcome happen for her. But we can’t. It’s beyond our power. That’s how real life works.

One could say that they may want more interactivity out of Cibele, or That Dragon, Cancer for that matter, but I don’t think “best game” means “most interactivity.” The simplicity is part of the beauty. I only have so much control over what I can and cannot do in these games. As much as I may want to, I can’t cure Joel or help Nina connect with someone. I don’t even have that much control over my real life, but if I want to I can help a sick kid down a slide or whack some virtual goons with my friends, even if that’s only in a video game. That's the kind of personal bond these games have to offer.

And who knows, maybe I can make that connection by hitting a giant ball with my rocket car. The only way to find out is to keep playing.